Above: Prince Harry with Paul Croft and Michelle Chatterley of the Create Education training agency (left and centre) and Marilyn Comrie and Nile Henry from the Blair Project (right)

Nile Henry is enthusiastic about what the Create Education training group has done for his organisation. “It’s had a transformational impact,” says Henry, chief executive of the Blair Project, which aims to inspire the next generation of engineers through making and racing electric go-karts.

Now, Create Education – based in Chorley near Manchester and which organises workshops for 3D printing throughout the UK – is planning a big extension in its activity. It intends to double in each of the next two years the number of courses it runs, to reach a total of up to 200 a year. Each course typically involves 15-20 people and lasts one to three days.

The group is at the centre of a diverse network of people throughout the UK, united by an interest in 3D printing, but with a range of backgrounds and goals. As a result, Create Education has brought together in education ventures a mix of organisations – including businesses, schools and community groups –that might otherwise have remained apart.

Create Education works mainly with teachers and young people. It focuses on 3D printing or additive manufacturing, a fast-moving technology for creating items in short production runs and with potential applications in industries from toys to aerospace.

The central idea is helping young people learn about engineering and technology. That aligns with the goals of Made Here Now, established to highlight innovative manufacturing and encourage more young people to consider this as a career.

“Giving children the chance to try out new thinking with an emerging technology [3D printing] is very valuable in equipping them with the sorts of skills they may need in the future,” says Michelle Chatterley, head of education at Create Education. The group employs seven people including directors, Paul Croft and Alex Mayor.

The emphasis on 3D printing makes sense since the technology – which provides ways of building up complex objects layer by layer relatively quickly – has captured the imagination of many young people. “Many school children find 3D printing hugely inspiring,” says Chatterley.

Also, it can be learned about using cheap desktop machines suited for schools, rather than the expensive and bigger “professional” systems used in industry.

The Blair Project is among the groups with which Create Education has collaborated. With Create Education’s help, in 2016 the Blair Project started using 3D printing and computer-aided design to create its own karts, cutting their cost from £6,000 to £1,000.

-,with-gocart.jpg) Racing karts made from 3D-printed parts are at the centre of programmes organised by the Blair Project, supported by Create Education

Racing karts made from 3D-printed parts are at the centre of programmes organised by the Blair Project, supported by Create Education

The changes enabled the project, named after Henry’s brother, to add a production and design element to its activities in organising kart racing. “They [Create Education] turned us into makers and got us to where we are today,” says Henry. His project often works with children from poor or socially disadvantaged backgrounds who might lack the opportunities to learn about engineering and technology.

Prince Harry has been among those interested in what the Blair Project does. The 34-year-old royal dropped in to the Three Sisters Racing Circuit in Wigan, near Liverpool, in 2016 to talk to people associated with the project, meeting Chatterley and Croft at the same time. Chatterley says of the Blair Project: “We have helped and supported each other.”

Another group to have worked with Create Education is Renishaw, an innovative UK company which is a big maker of specialist measuring probes and related instruments, while also producing its own brand of 3D printing machines. With 3,000 employees in the UK, where it does nearly all its production, it runs an extensive schools programme designed to boost interest among young people in engineering.

Simon Biggs, a former teacher who is Renishaw’s education centre outreach officer, describes Create Education as “a very professional group of people who offer fantastic resources for the teaching community”. He adds: “There do not seem to be many comparable companies to Create, so they continue to be the ‘go to’ education provider for support and help [in 3D printing].”

As well as Renishaw, Create Education organises courses and events in conjunction with other businesses including Autodesk. The big US-based provider of design and manufacturing software was among the participants at a three-day training session for 300 young people organised by Create Education in September 2018. The event was organised with media group TCT at its big 3D printing exhibition in Birmingham, with another collaborator being Bloodhound, a project started by Richard Noble to build a supersonic-speed car.

Children learn about 3D printing at Renishaw’s education centre in Miskin, south Wales

Children learn about 3D printing at Renishaw’s education centre in Miskin, south Wales

According to Chatterley, interest sparked by such ventures is increasing demand for Create Education’s services. From the 50 or so courses and related events it operated in the year to September 2018, it hopes to push this to 100 in 2019, with the figure possibly doubling again the year afterwards.

Often, she says the most useful way in which Create Education can assist on schools’ projects is to focus on teachers: “However good and enthusiastic teachers are they can sometimes be a barrier to helping children learn – particularly about a new and evolving technology. That’s why it’s important to give teachers the skills they need to help children learn.”

A good example of how some of the projects supported by Create Education can involve a mix of entities is a school’s programme in Plymouth organised by Plymouth Manufacturing Group, a partnership of Plymouth-based business.

The PMG – among the UK’s most active regional industry associations – wanted to boost awareness among local children about career opportunities in engineering.

A good way to do this, it reckoned, was through focusing on 3D printing, in a scheme assisted by Create Education. Also involved were several Plymouth manufacturers and FabLab Plymouth, a digital fabrication facility at Plymouth College of Art. Gemma Selley, a PMG consultant, says Create Education provided “fantastic support”, ensuring that children participating in the scheme gained useful experience.

A key factor in Create Education’s progress is that it supports its education services through a separate venture, selling equipment and services from other companies. These include the Netherlands-based 3D printing machine producer Ultimaker; Printlab, which provides curriculum materials in digital manufacturing; and Filamentive and Innofil3D, two UK-based suppliers of the filament materials used in 3D printing.

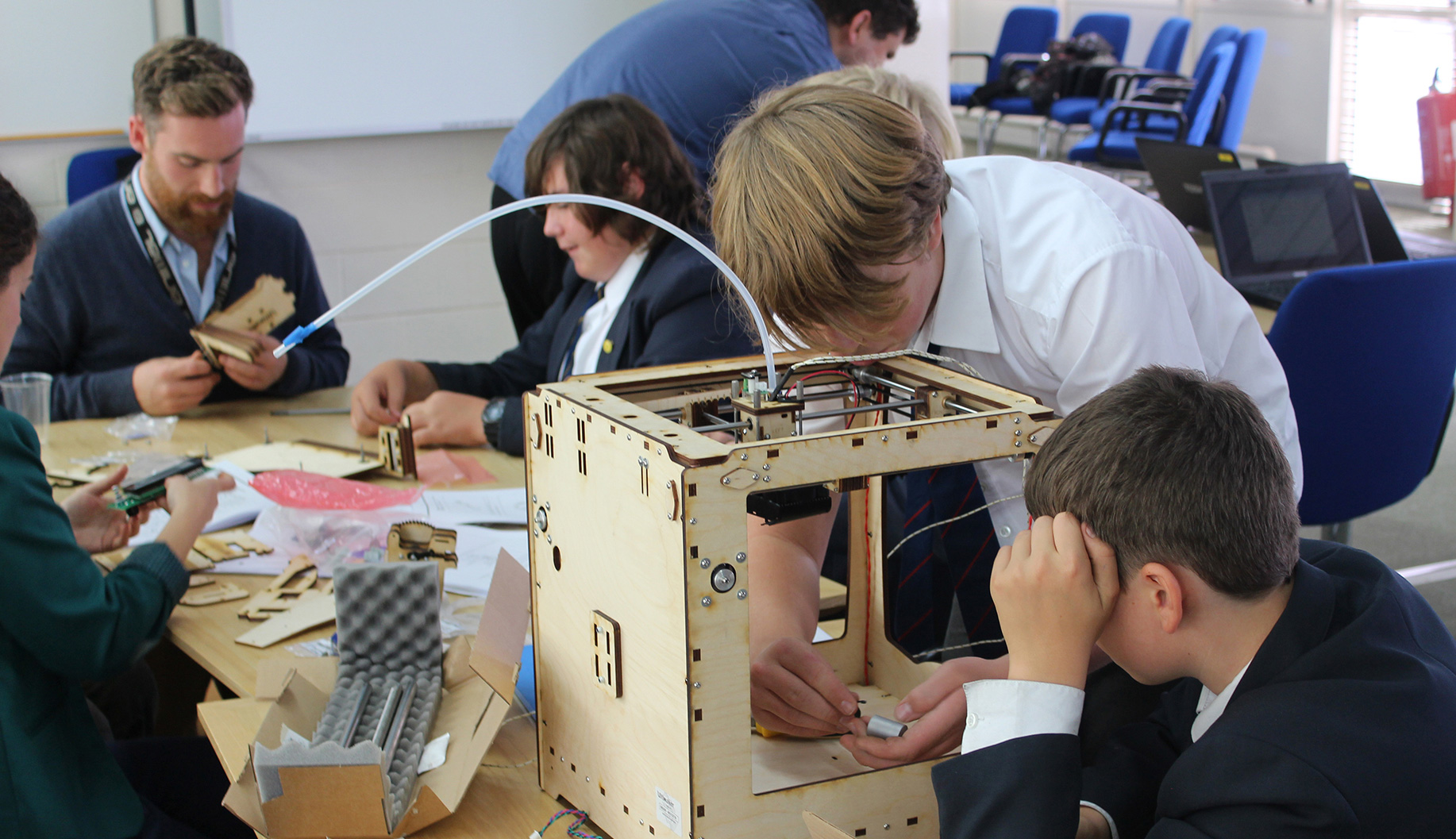

Small desktop machines for schools give young people practical experience of modern design and manufacturing

Small desktop machines for schools give young people practical experience of modern design and manufacturing

The commercial operations provide income which enables Create Education to cut the cost of courses it runs. It provides some of them for free – an attraction for many schools hit by cuts in education budgets.

Outside the commercial sphere, Create Education has links on training projects with a range of other organisations with wider social aims. These include the Crafts Council, a leading charity for craft-based production; Barclays Eagle Labs, a network of workplaces for entrepreneurs financed by Barclays Bank; and ECraft2Learn, a European Union-wide group backing small ventures in digital fabrication and other novel areas of production.

Additive manufacturing may help tutor tomorrow’s engineers

Additive manufacturing may help tutor tomorrow’s engineers

Small community-based “maker workshops” with which it has worked include FabLab Sunderland, iForge in Sheffield and MakerNow in Penryn. It has also collaborated with MakerVersity, a London-based group that operates workplaces for manufacturing and tech-based entrepreneurs, and Tech Will Save Us, an unusual operation that makes toys and technology kits for children combining teaching and play.