Aircraft and defence equipment are among the sectors Craig Wright has targeted as customers for his company’s high-tech electronic products.

High-flying former pilot avoids Brexit headwinds and charts expansion

Brexit has involved unavoidable costs but the long-term benefits for the UK will outweigh the difficulties, says

Craig Wright who runs an unorthodox manufacturer and is unafraid to take a minority view.

Through his flagship company Wright Industries, Wright owns and manages UK industrial businesses that the former RAF

pilot expects to have combined sales in the year to June of £52m, up from £36m in 2021-22.

He has little time for the often-held opinion among manufacturers that the UK’s European Union departure has been

damaging. “We [Wright Industries] have 650 customers that are mainly large businesses operating worldwide,” says the

54-year-old, whose early qualifications were not in technology but accountancy.

“When they talk to me, no one has Brexit on their list of concerns. They want to discuss whether we can make and

develop products for them in the UK and increasingly the answer is ‘yes we can’.”

He adds: “Brexit gives the UK the opportunity to operate its own policies that are in the national interest rather

than fitting EU regulations. In manufacturing and engineering, the government has the chance to organise its own

investment and development projects tailored to sectors and technologies specific to the UK.”

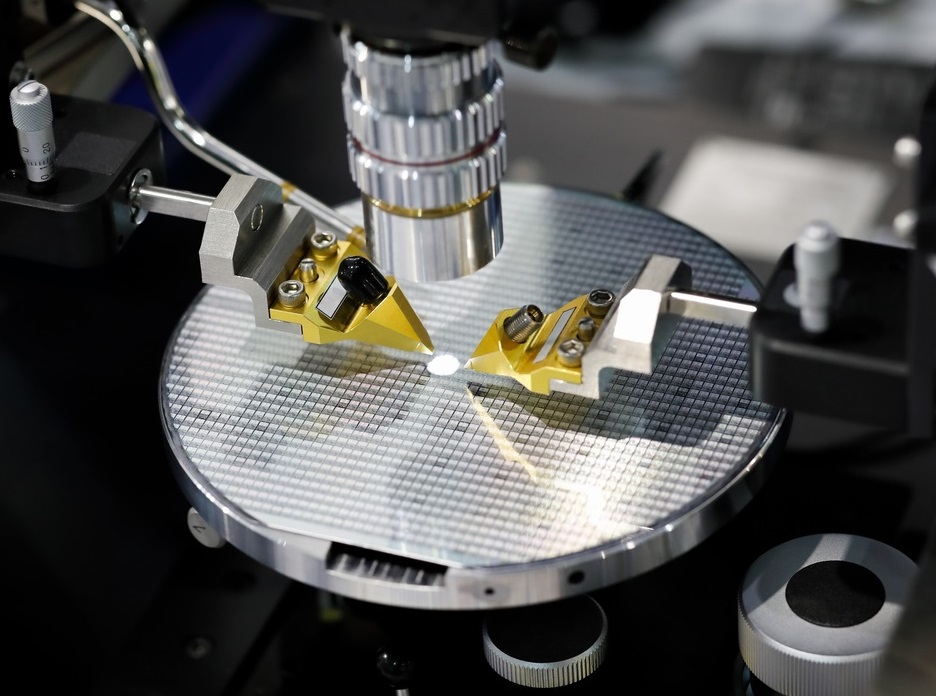

The companies in Wright’s group make a range of high-tech electronic products - largely specialised components made

in small volumes that fit inside bigger pieces of equipment in sectors including aerospace, medical, defence and

power management.

The components turned out by Wright’s companies are mainly made in small volumes and fit inside other businesses’ equipment.

The components turned out by Wright’s companies are mainly made in small volumes and fit inside other businesses’ equipment.

With 350 employees, mainly in the UK, increasing from 260 prior to the UK’s departure from the union in 2020.

Wright’s holding company has just one director – himself – and both published contact numbers for the business

in London and Birmingham connect to his mobile phone.

Individual companies in the group are run by seasoned executives who Wright trusts to get results. “[It’s] not

your conventional model but it works,” says Wright who set up his holding company in 2011 after previously

running and owning Exception Group, another specialised electronics business based in Wiltshire.

In his views about Brexit, Wright - who likes to adopts a low profile and does not court publicity - is a

relatively lonely voice among UK manufacturers. In a Made Here Now survey from last year, of the 54

manufacturing executives, only three – including Wright – said the EU departure had had a positive impact on

their companies. Of the total, two thirds said Brexit had harmed their enterprises, due to factors such as

higher costs and more complex supply chains. The rest took a neutral stance, citing a mix of good and bad

outcomes.

The overwhelmingly negative view in the survey echoed other polls of businesspeople and reinforced government and

academic reports indicating that the UK’s leaving the trading bloc had weakened the economy.

While Wright does not deny that some businesses feel Brexit has been negative, he believes that many

manufacturing bosses are too ready to blame the change for a range of setbacks. “Brexit was always going to

involve [initial] costs,” he says. “But I think a lot of commentators are confusing the impact of the EU

departure with the economic problems caused by other factors including the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine.

The world economy is being affected by several challenges of which Brexit is one.”

Companies in Wright’s group use the umbrella brand Connexion Technologies and include Custom Interconnect, Accura

Engineering, Pure Electronics and Castle Microwave. The main production and development bases are in

Wolverhampton, Andover, Newbury and Chippenham, with other operations in east Asia.

Wright reckons that more job opportunities within his companies will arise in the future as they expand on the

back of strong order inquiries and a £15m capital investment programme. Among the new projects is a £10m plant

in Andover to package semiconductor devices using novel materials for electronic substrates such as silicon

carbide, designed to cut energy use.

Wright says this will be the first factory of this type in the UK, as semiconductor packaging - a key step in

electronics manufacturing in which the finished microchip is put inside a protective casing - is usually done in

east Asia.

While the number of big UK electronics and electrical goods manufacturers has fallen sharply in the past 30 years, the sector continues to be represented by smaller enterprises making specialised items.

While the number of big UK electronics and electrical goods manufacturers has fallen sharply in the past 30 years, the sector continues to be represented by smaller enterprises making specialised items.

Supporting his view that his companies’ turnover could double in the next two years, Wright says Brexit, rather

than being a source of problems, may already be having some positive effects. “Brexit is one of several factors

- the others including Covid and the war in Ukraine - encouraging global companies to look more closely at

countries such as the UK, with its great engineering strengths, as a place for technology development and

production.”

He claims also that leaving the trading bloc has made UK government bodies keener to provide financial

support to UK businesses developing new technologies that promise more wealth and jobs:

“In my experience of UK manufacturing - and I’ve operated companies through four recessions with a fifth one

apparently being on the way - prior to Brexit I’ve received no government support for any of my businesses.

However, since Brexit I’ve been encouraged by the government approach towards technology assistance.”

Wright gives as an example his company’s relationship with the Advanced Propulsion Centre, a

government/industry research and development organisation based in Coventry. The centre’s main role is to

help the automotive industry move to low-carbon propulsion, for instance through electric or

hydrogen-powered vehicles. In partnership with the centre – together with two UK innovation agencies,

Warwick Manufacturing Group (part of the University of Warwick) and the government’s InnovateUK - Wright

Industries is taking part in a £12m development programme into advanced electronic control equipment with

roughly half the costs coming from the government.

“The products likely to emerge from the project have applications in a range of industries that use electric

power including not just cars but data centres and aircraft,” Wright says. “The support is enabling us to

stay at the forefront of a technology [electronics control] to which many big businesses around the world

are paying a lot of attention.”

Overall, Wright has a bullish stance on the future for UK manufacturing: “Nobody nowadays is doing what they

did a few years ago and discussing closing plants in countries such and UK, in favour of opening new ones in

China.” But he says more needs to be done to ensure that components such as those made by his group are used

in assembly operations in factories based in the UK rather than in other countries.

“Mainly the items we [Wright Industries] make are bought by non-UK companies. They finish up being assembled

with other components in overseas factories. Where the UK needs to do a lot better is in making it less

necessary to transfer such parts to other countries to put them to use. We need to do more to keep

manufacturing in the UK.”